FutureBrand’s redesign of Massimo Vignelli’s classic 1968 American Airlines logo and livery is the first big identity design news of the year. How does the new “Flight Symbol” relate to larger trends in U.S. logo design? Let’s investigate…

The most obvious change from the old American logo is the switch from a stylized depiction of an eagle in flight to an abstract version. By going abstract, FutureBrand has dealt with a couple of nagging problems related to using birds in airline logos.

from Communication Arts, January 1963

The first is that airline bird logos have long been clichéd. Even a half-century ago, in 1963, a Communication Arts article detailed the work of designer Jim Cross in redesigning the identity of aerospace giant Northrop (now Northrop Grumman). Cross, noting the overabundance of birds in flight in aviation logos, did away with Northrop’s bird symbol and replaced it with a simple wordmark.

Secondly, airline bird logos reek of old-fashionedness. Discussing his work for United Airlines in a 1981 Los Angeles Times interview, the legendary Saul Bass noted, “Almost all airlines begin with a birdlike mark, but when we leap into jet technology, the safety factor becomes more important. You can’t go around with flapping birds any more.”

American’s new Flight Symbol is sufficiently abstract to mitigate these concerns.

Interestingly, it seems that had Vignelli had his way, American would have dropped its bird long ago. As he related to Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Vignelli did not want to include the traditional American eagle in the logo unless it was depicted fully realistically, so Henry Dreyfuss was enlisted by American to shoehorn an eagle into the design.

Some insight into the origin of the Dreyfuss eagle comes from a 1969 New York Times interview, in which Dreyfuss argues that “Designing a trademark is one of the most difficult things in the world. You have to become completely saturated in what you’re doing.” Reporter Philip Dougherty notes that Dreyfuss then “confided that American’s new mark was born on a paper napkin in the Plaza bar and one began to wonder just what kind of saturation he was talking about.”

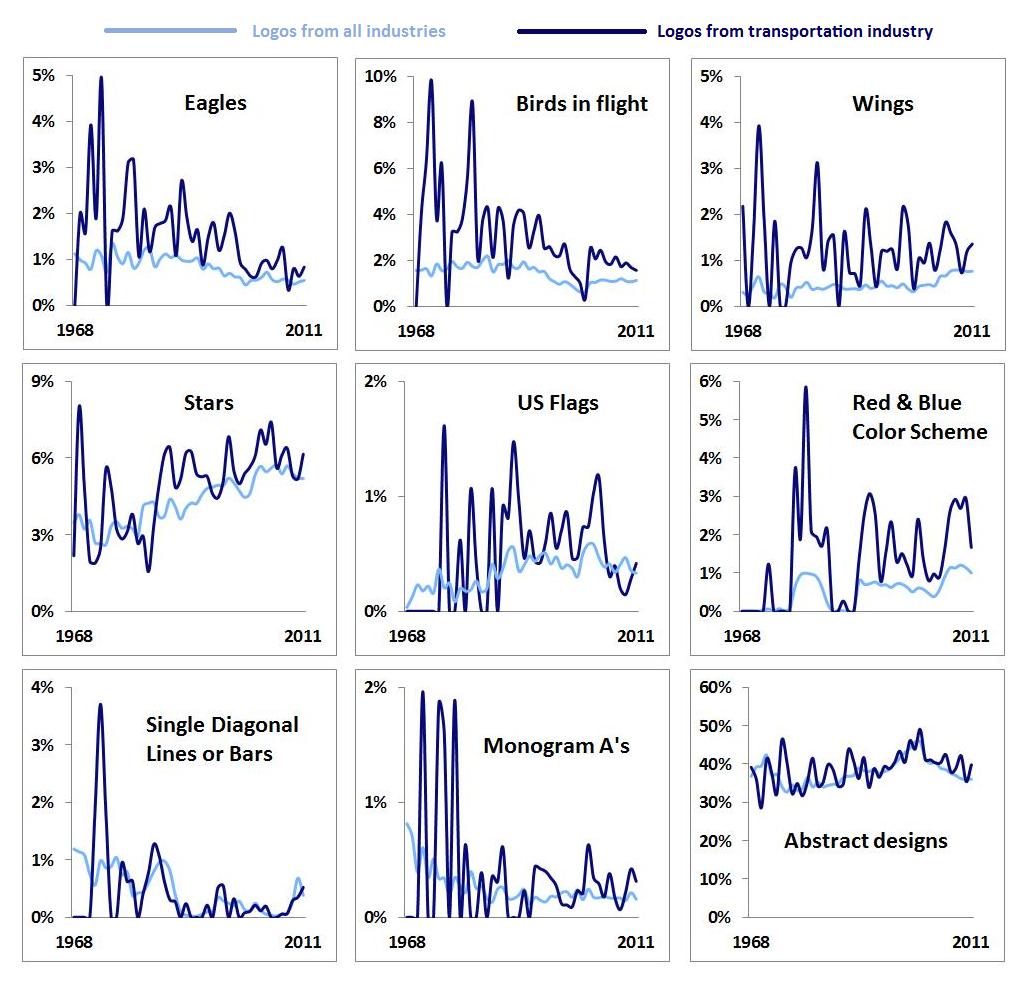

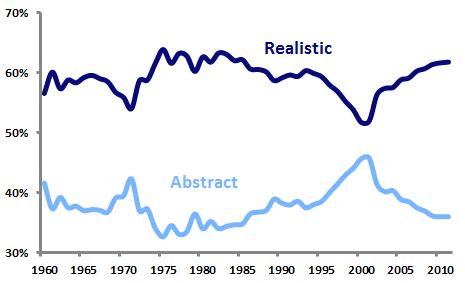

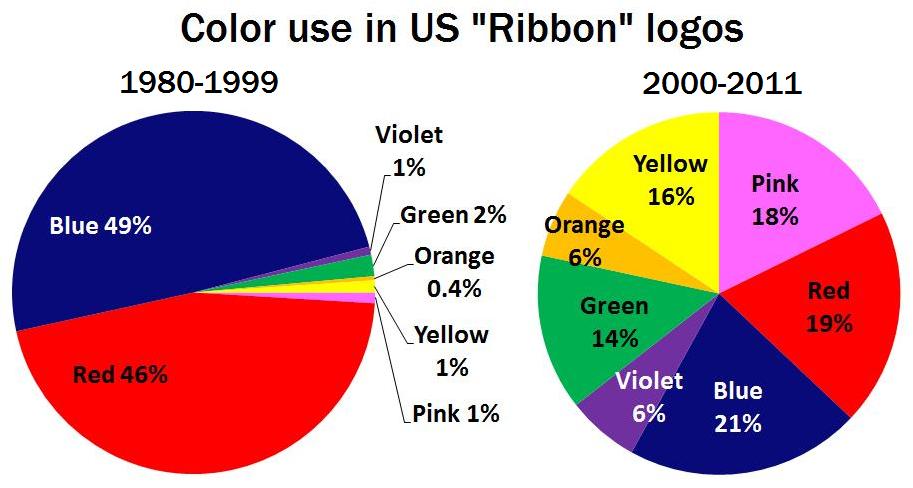

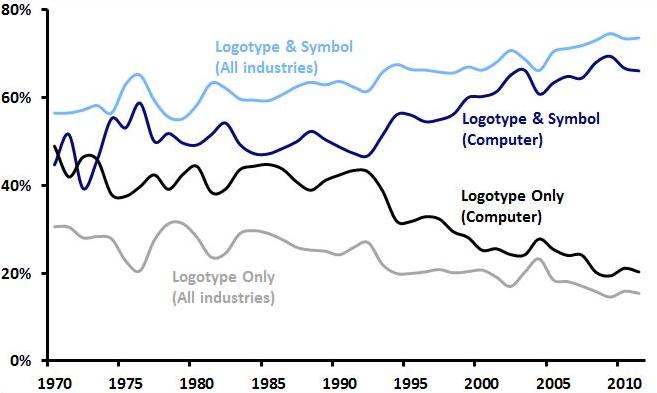

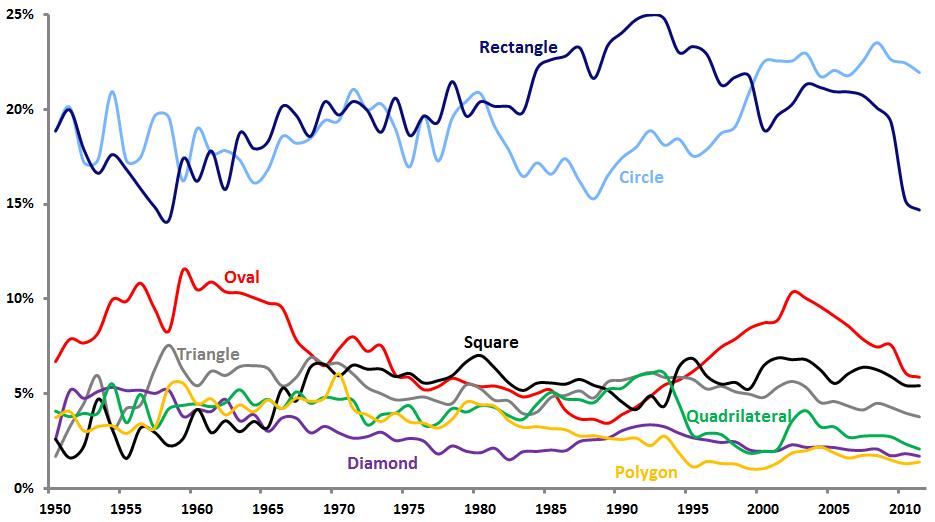

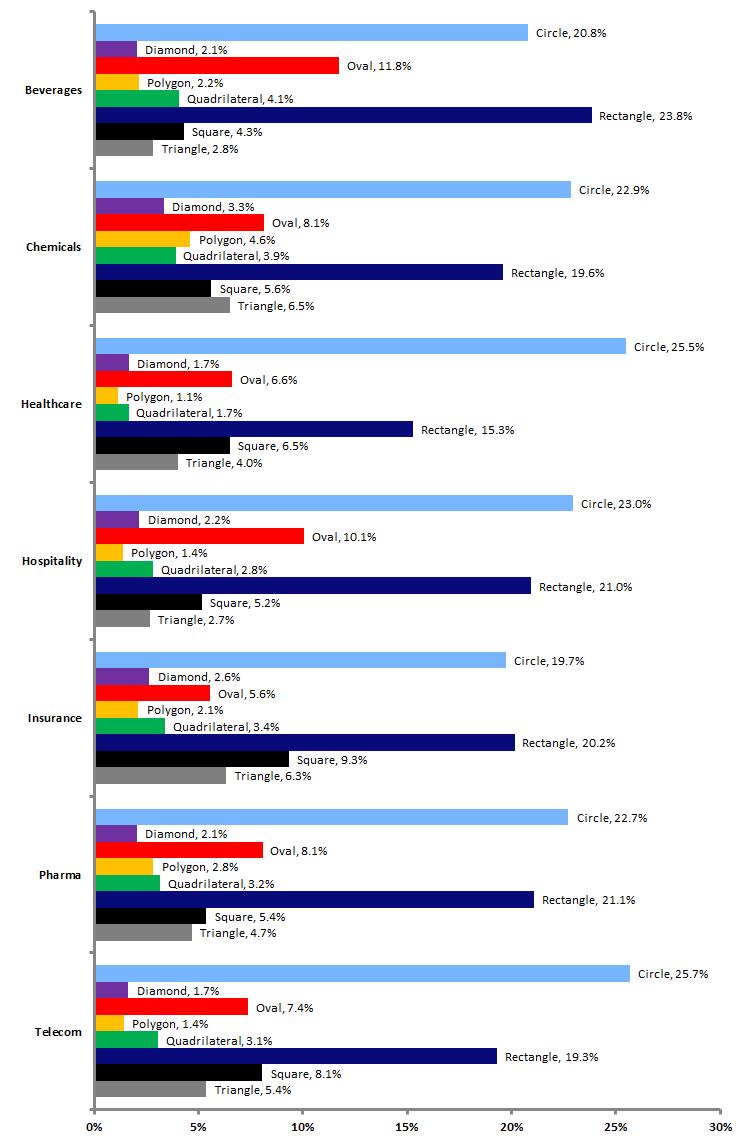

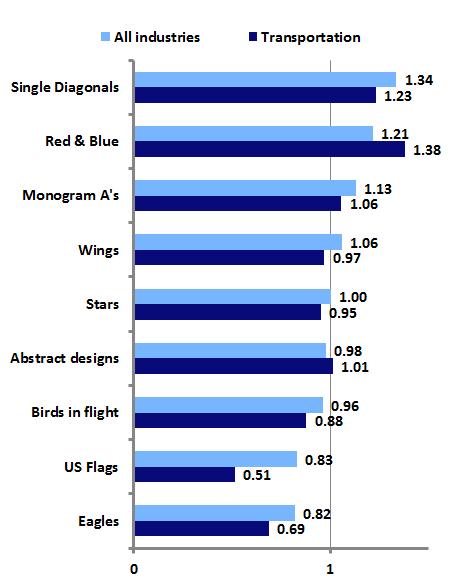

In its abstraction, the new Flight Symbol is able to suggest elements beyond the flying eagle, such as a star and an “A” monogram. The design also incorporates a red-and-blue color scheme, the U.S. flag (on the plane’s tail), a single diagonal element, and it is abstract in general. Analysis of United States Patent and Trademark Office data allows us to assess the relative use of each of these design elements since 1968 among logos of all industries and those of the transportation industry in particular.

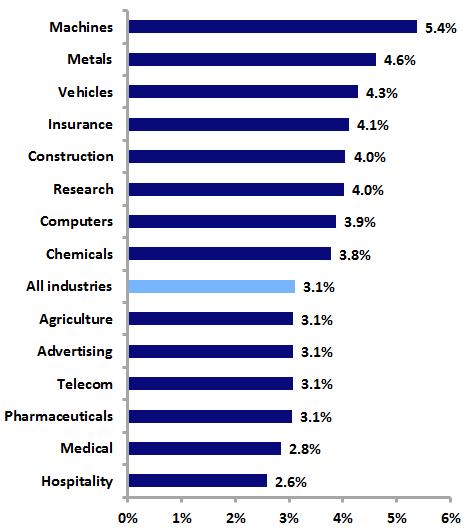

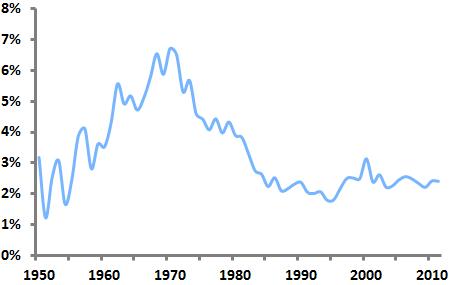

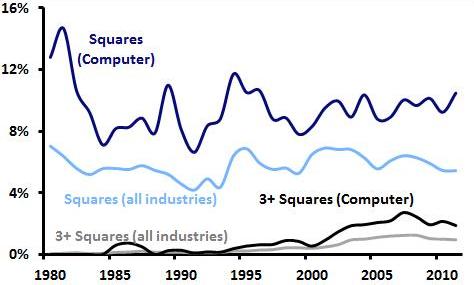

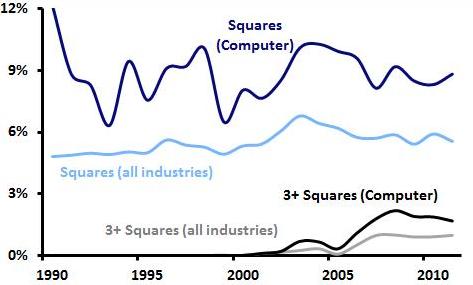

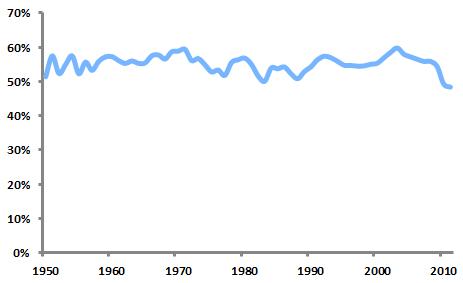

Percentage of new US logos featuring specific design elements

The associated avian design characteristics (eagles, birds in flight, wings) seem to be declining both in general and in transportation industry logos in particular. In order to preserve the visual heritage of its logo, American must employ design elements that imply a certain datedness. As noted above, however, the abstract nature of the Flight Symbol helps to allay these concerns. Other elements, such as stars and U.S. flags, have enjoyed somewhat more common use in recent years.

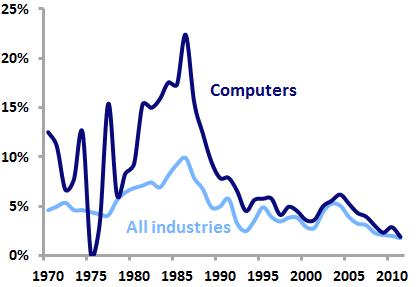

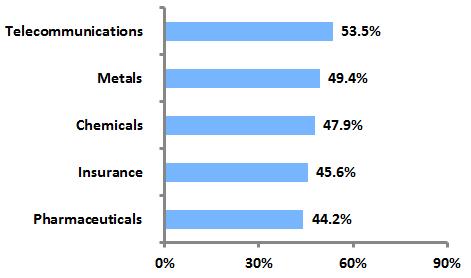

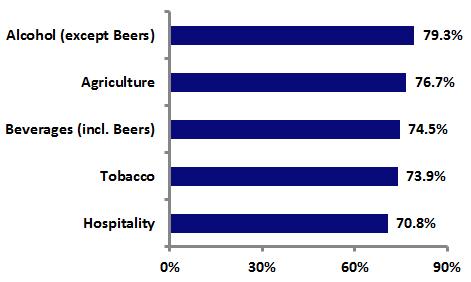

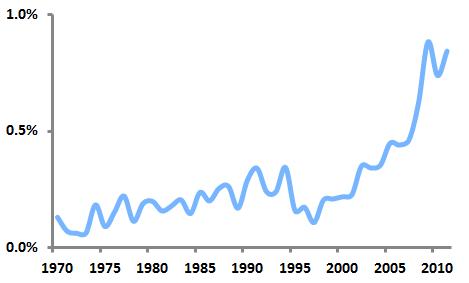

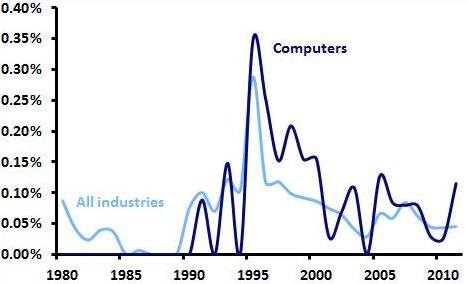

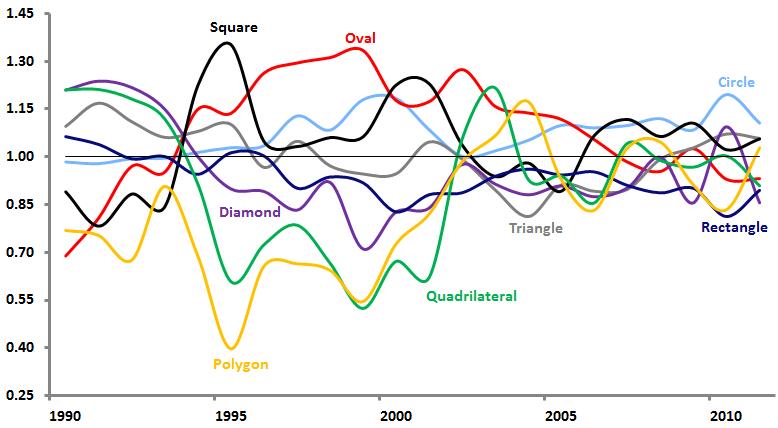

We may extend our analysis by looking at the “trendiness” of these design elements, which can be measured as a ratio of the share of each element among new logos from the last five years to the share of each element among “dying” logos over the same period. Using such a measure, values above 1 indicate design elements that are relatively “hotter,” while values below 1 suggest “colder” design elements.

“Trendiness” of design elements, 2007-2011

As the graph above shows, the “hottest” aspect of the design is the single diagonal, which is essentially the only new element added to the old Vignelli/Dreyfuss identity. This suggests that FutureBrand has done a good job of implementing a contemporary look that nicely augments and preserves American’s traditional identity, weighted down as it is with somewhat dated elements.

As the graph above shows, the “hottest” aspect of the design is the single diagonal, which is essentially the only new element added to the old Vignelli/Dreyfuss identity. This suggests that FutureBrand has done a good job of implementing a contemporary look that nicely augments and preserves American’s traditional identity, weighted down as it is with somewhat dated elements.