June is Pride Month, and the most visible manifestation of this celebration of the gay community is the rainbow–in particular, the Rainbow Flag designed by Gilbert Baker in 1978. In recent Junes, the flag has gone mainstream as companies such as IBM have rolled out rainbow versions of their logos to honor (or co-opt) the Pride movement.

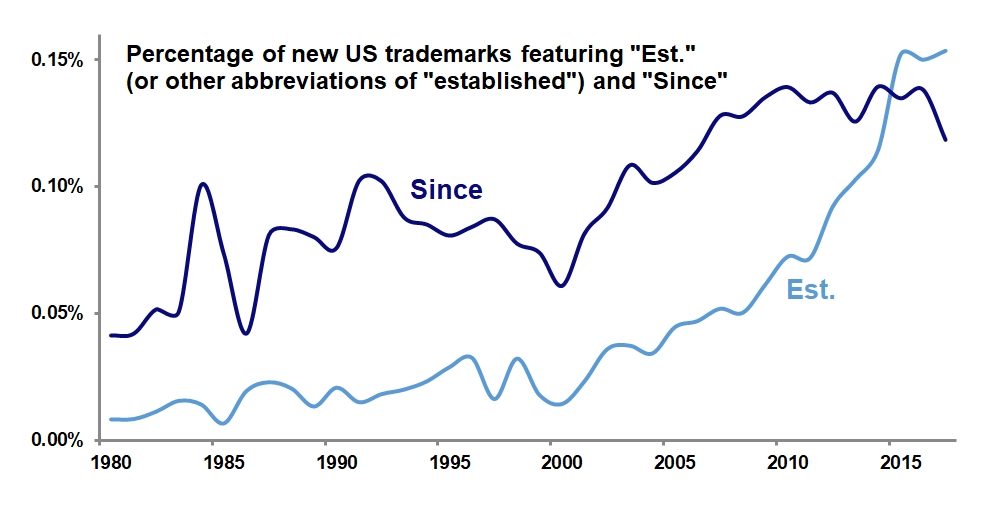

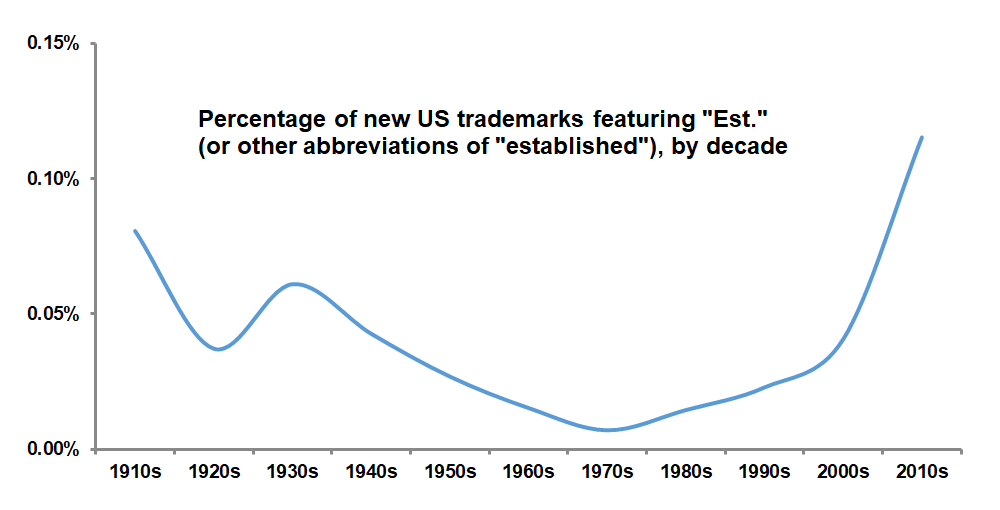

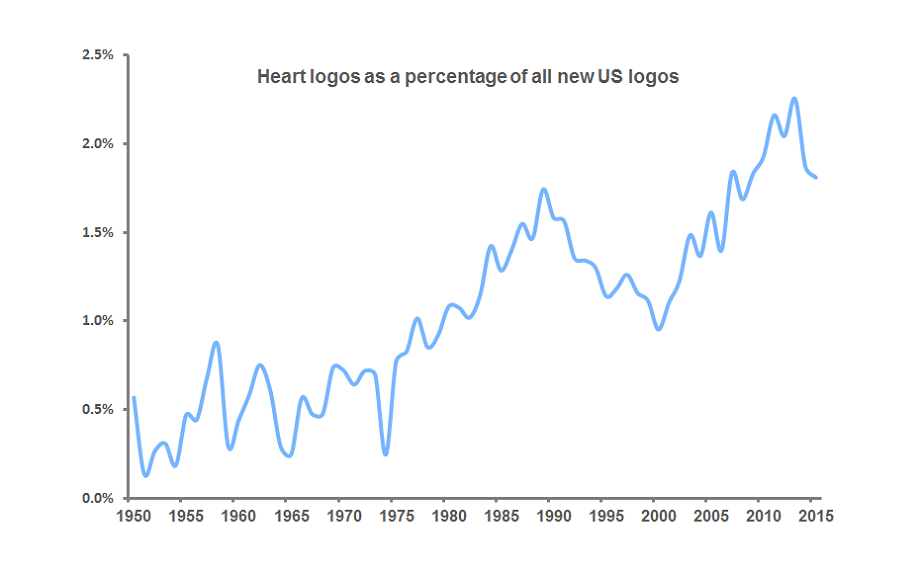

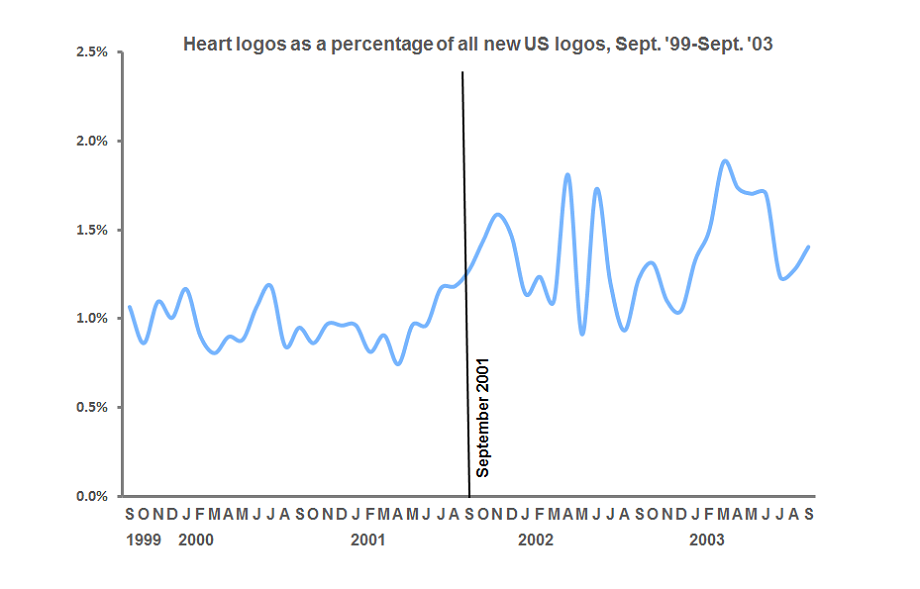

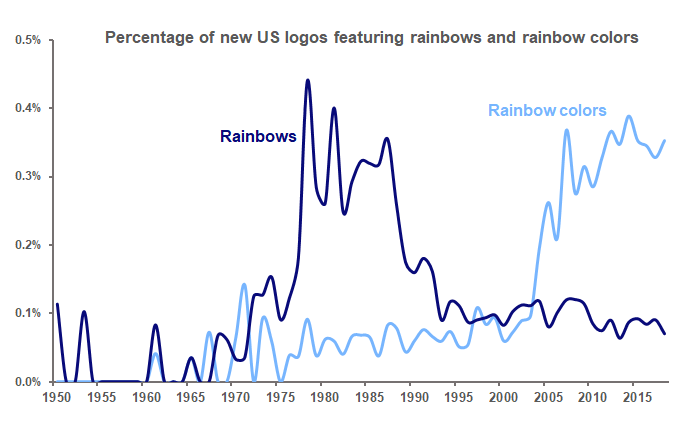

The use of rainbows in commercial symbolism is a relatively recent phenomenon. Analysis of United States Patent and Trademark Office data (see below) shows that, prior to the late 1970’s, very few American logos featured rainbows. Saul Bass’s 1972 United Way logo was a notable exception, and Rob Janoff’s 1977 Apple mark, with its famously out-of-order colors, helped bolster the trend. In 1978, as Baker sewed his first flag and Robin Williams’s Mork from Ork first graced American airwaves with his rainbow suspenders, the popularity of rainbow logos suddenly spiked, and remained high throughout the 1980’s.

Early uses of rainbow colors in logos often specifically emphasized color as a product feature: NBC’s peacock highlighted the network’s color broadcasts, and Apple’s logo touted the Apple II computer’s color graphics capabilities. But the positivity and cheerfulness communicated by the rainbow make it an attractive choice as a general design element.

Of course, the rainbow’s appeal is based in color; designers’ early aversion to rainbows was likely due to the fact that logos often had to be presented in black-and-white media such as newspapers and fax. Throughout the 1980’s, this black-and-white world was still a reality, so rainbow logos had to be readable as rainbows even without color; hence, the familiar semicircular shape.

But in more recent years, as technological advances have brought color to almost every medium, the spirit of the rainbow can be communicated through its colors without the need for its explicit shape. Consequently, the use of rainbows as logo design elements has fallen back almost to its pre-1970’s level, while the use of rainbow colors in logos has taken off.

Today’s rainbow-colored logos reflect the joy and optimism inherent in the rainbow in a multitude of new expressions.